I'm going to broiler farm for avian trip. Here's the chief complaint.

****************************************************************

Same age but different growth stage

Runting and stunting syndrome

Few things are well defined regarding runting-stunting syndrome. Starting by its very name, “runting stunting” is poorly defined and will probably be changed in the future depending on the etiological agent o agents identified. In poultry, a “runt” is defined as an animal that is unusually small, especially the smallest of a flock. “Stunting” relates to the hindering of the normal growth of an individual. Thus, “runting-stunting” can be defined as a syndrome in which a number of individuals in a flock appear considerably small due to delayed growth. The larger the number of chickens that are unusually small, the lower the body weight average for the flock.

Runting-stunting syndrome (RSS) has been recognized for many years and was first described in the 1970s. One can think of a seemingly endless list of possible causes for RSS, including faulty poultry genetics, management, environmental challenge, feeding and nutrition, infectious disease and perhaps other reasons and any possible combination of them.

Although some features of RSS have been reproduced upon experimental infection with reovirus, the general consensus is that these viruses are unlikely to be the sole culprit in RSS. Small round viruses (small within the context of general virology) have been visualized many times in the intestines and intestinal contents of affected broiler chickens using electron microscopy, but such viruses can also be found in nonaffected flocks or individual chickens.

This condition is usually seen between 3-6 weeks of age and is usually observed in meat type chickens.

Brooding at cool temperatures tends to worsen RSS symptoms, as does short down-time between flocks. Certain strains of birds appear to be more susceptible to the effects of RSS than others and male birds are more severely affected than females (Zavala and Barbosa, 2006). However, it is interesting to note that researchers have found that resistant broiler strains have stronger immunological responses than susceptible strains. This difference is particularly pronounced when gut immunity is compared (Rebel et al., 2006). Some researchers have suggested that the poor growth and retarded feathering (which are consistently observed in RSS cases) are due to a common underlying infection, while virtually all other symptoms result from other infections or management factors.

Clinically, affected flocks show large numbers of immobile chicks huddling around the feeders and drinkers within hours after placement. Some may peck incessantly at the walls. The litter quickly becomes damp and chicks may exhibit matted down in the abdominal area as a result of resting on wet litter. Consumption of chick starter feed typically lasts a day or two longer than usual. As early as 6-7 days of age many chicks will already appear stunted, pale and sometimes disoriented, but the usual peak of the problem occurs at around 10-12 days of age. The bodies of affected chicks will look small relative to the length of the primary feathers of the wings and beak. A small number of affected chicks may display “helicopter” feathers in their wings and other feather abnormalities.

“Helicopter” wing feathers

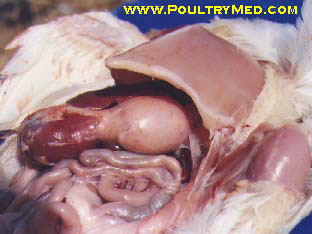

Some of the internal gross lesions or changes that have characterized recent cases of RSS include (not exclusively): small livers with a grossly enlarged gall bladder; pale, thin, almost translucent intestinal wall with wet pellets of undigested food that is visible through the intestinal wall; large amount of fluids inside the small and large intestines; infrequent feed impaction in the cloaca; occasional increased amount of pericardial fluid; sporadic white or cream-colored plaques in individual proventricular glands.

Proventriculitis or proventricular distension. The poventriculus is large almost as the gizzard.

Diffuse enlargement of the poventriculus due to thickening of its wall.

Normal (left) and affected (right) poventiculus.

Various microscopic lesions have been described but the most frequent one is the presence of multiple cysts involving the intestinal crypts. The early lesion can described as “cystic enteropathy” and as it evolves into an inflammatory lesion it turns into “cystic enteritis”. The nature of the inflammatory responses suggests a viral etiology rather than bacterial. As the lesion progresses it may result in shortening and clubbing of the intestinal villi. Other microscopic lesions are important observations but they are not always present in cases of RSS. Viruses, nutritional deficiencies and parasites have been proposed as possible etiologies of cystic enteropathy. Until now, only deficiencies of some complex B vitamins (thiamin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and niacin) have consistently reproduced cystic enteropathy.

Treament

No treatment available

Control

When RSS is reported in an area, it is important for the industry in the area to tighten Biosecurity procedures to reduce the possibility of exposure and to slow the spread of the disease. It is particularly important to emphasize procedures that control farm visitors, properly manage disposal of mortality and limit vermin infestations (rodents, wild birds and insects).

The objective of proper poultry house management is to provide an environment for the birds that is virtually stress free. In RSS situations, poultry house management is doubly important. Good management starts before the birds arrive. A minimum of 12 days of downtime should be allowed between flocks. Since litter has been shown to transmit the disease, it should be removed if birds have broken with RSS. If it is not possible to remove the litter, heat the litter to 100°F for 100 hours or compost the litter in the poultry house to lessen the possibility of passing the disease to the next flock via litter. The brood chamber should be cleaned and disinfected as thoroughly as possible prior to chick placement. Since low brooding temperatures have been shown to worsen the effects of RSS, DO NOT reduce brooding temperatures to save fuel. Check on birds often and maintain a house environment that is as stress free as possible. Remove dead birds quickly and cull severely if RSS breaks. The application of vinegar or other acidifiers via water may reduce spread of the disease. Supplemental vitamins and minerals in both breeder and broiler feeds has also been shown to improve immunity in chicks and their ability to deal with RSS.

Certain strains of reovirus (e.g. 1733 and 2408) were originally implicated as the cause of RSS and vaccines have been developed for such strains. While vaccination of broilers for RSS may be effective about 50% of the time, a consistent vaccination program for breeders often provides long term benefits (Shane, 2008, van der Heide, 2000). RSS vaccination programs for breeders generally provide protection for adult birds, reducing the possibility of spread to young birds. In addition, immunity in breeder hens is passed to chicks, helping to protect them from the disease

Sources

The poultry informed professional; www.poultry-health.com, Runting and stunting syndromes in broilers; www.poultrysite.com, REO Virus (Runting and stunting syndrome)www.vetsoft.com, Runting ans stunting syndrome; www.poltrymed.com